Over the last five years, colleges and universities have become increasingly aware of the need for an effective emergency notification system for campus threats. In addition to issuing notifications via email, SMS, Twitter broadcasts, and the campus radio station, the school had a system in place that relied on a single person to publish notifications to their website in the case of an emergency. However, when the last campus emergency took place while this person was unavailable, the web team realized a need for an automated system. Hannon Hill spoke with Erick Beck and Michael McGinnis at Texas A&M University to learn more about how they use Cascade CMS to power automatic updates to their full site, their emergency site and their mobile site during emergency situations using a system that they call Code Maroon. Below you will find the questions we had for him, followed by his answers.

Q: What is a Code Maroon and what are some examples of why one would be issued?

The 2007 Virginia Tech shooting fundamentally changed the way higher ed treats and responds to emergency situations. Almost overnight, universities had to find and implement a way of providing instant updates to the public in dangerous situations. Code Maroon was our solution. A Code Maroon alert is issued any time an incident occurs which the university police or campus safety team deems a threat to campus. This might be anything from an armed gunman to a gas leak in one of our buildings. It began as an SMS text message system, but has since grown to include mass email, RSS feeds, Twitter broadcasts, and now automated integration with the university's major websites.

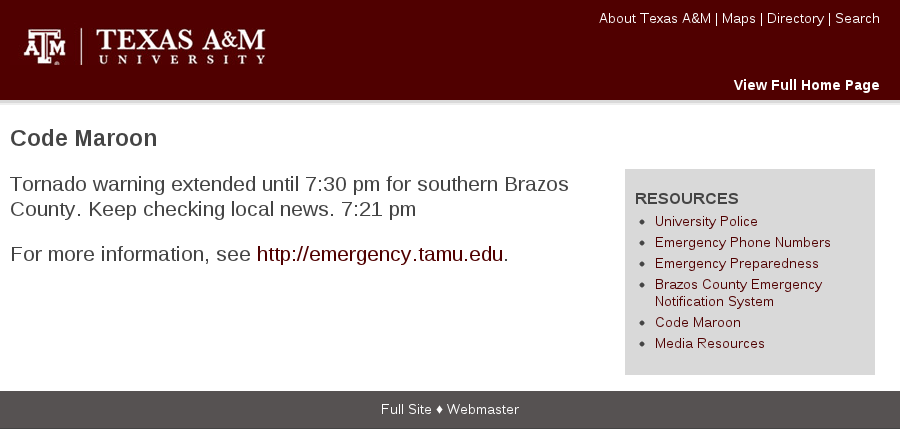

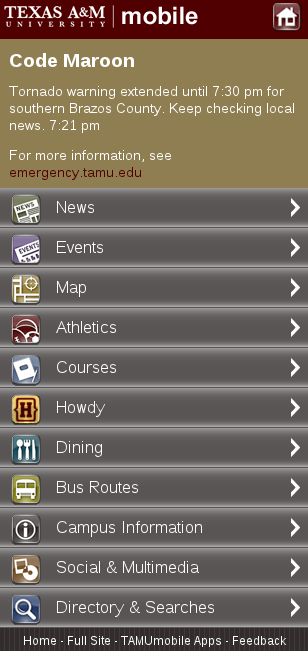

Texas A&M University Website Showing the Code Maroon Emergency Notification

Q: To which sites does the Code Maroon emergency content get published?

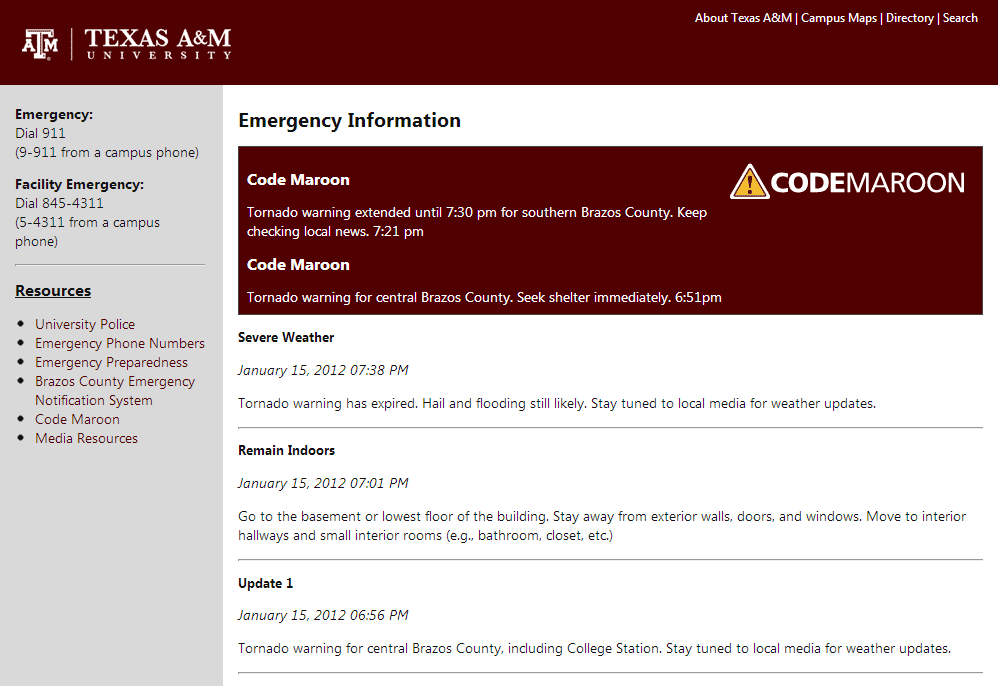

Alerts are now posted automatically to our university site, emergency site and mobile site. The mobile website uses a different process though; only the university site and emergency site are updated through Cascade CMS's web services. On the university site and the mobile site, users will see the latest Code Maroon alert and instructions to go to the emergency site for additional information. The emergency site will keep a list of all of the alerts posted during the incident, as well as additional updates from campus safety personnel which provide more detailed information than can be sent in a text message.

Q: What steps did you take to implement this functionality?

In the past, we updated our websites manually whenever there was a Code Maroon alert. To automate the process, we broke it down into two steps and tackled each one separately. First, we created a scheduled job that would query the Code Maroon RSS file, watch for updates, and send the content of a new alert to the web service API. Second, we wrote the API programming that would actually update the page content and publish the page. One of our staff was already registered to attend the Hannon Hill User Conference, and we sent him with a list of questions to ask during the one-on-one consulting session. This was quite helpful and he returned with a lot of good insights that made finishing the application much easier and faster.

Q: What was the timeline for planning, building and implementation? Who was involved in this process?

We were not given a formal timeline. The decision to automate the process was made after a Code Maroon event earlier this year. Several issues came together to prevent us from immediately posting the alert to our web sites using our manual process. The after-action report determined that we should move toward automating the process “as quickly as possible.” The planning stage took longer than building and implementation because we had to get input from several teams across campus. We met with the university Code Maroon project developers as well as the emergency response team to discuss technical requirements and deliverables. Once we had that direction, the actual coding went quickly. Overall, we spent a bit over a month on the project, developing several working iterations.

Q: Why did you choose to implement using Web Services instead of dynamic updating?

This decision was motivated both by our server environment and by our project requirements. Both the university site and the emergency site are static HTML. We try to tune our servers for performance, so many services, such as PHP, are intentionally not even installed. Since content is handled by Cascade CMS, site-wide include files are no longer necessary, so we have also disabled server side includes to help maximize efficiency. These things meant, though, that we could not use in-site scripting or even run a cron job to update an include file that could be displayed on the site. We also eliminated Javascript as an option. The emergency site was set up purposefully to be very lean (less than 10K.) It includes only one HTML page, uses internal CSS rather than requiring a separate file download, and puts all images on a single sprite. We designed the site like this because of its nature—as the emergency information location, it would need to handle the traffic spikes created by a large crisis event. We don’t want to drop traffic during a crisis, and having to load something as heavy as jQuery could easily cause a site to slow down under heavy traffic.

Finally, we wanted to be able to maintain an audit trail of all updates. After an event, there is always a post-mortem of the process, and we need to be able to go back and look at exactly what was published at any particular time. This information gets lost if it is simply embedded dynamically into the website with a script. We needed something that would create a permanent record of the alert being issued and published, and Cascade CMS's web services API and version tracking was exactly what we were looking for.

Q: Based on your experience, is there anything you would do differently if you were doing this again?

Probably not. We have had to make some minor tweaks, but overall, I am very pleased with our final product. It was, in fact, put to the test sooner than expected. In one of those “truth is stranger than fiction” moments, the university received a bomb threat the day after our automated solution was put into place. This turned into the largest emergency situation the university has ever faced. Everyone, including the web team, was required to evacuate on foot to off-campus locations. This left us with no one in the office who could have made real-time manual posts if the automation process didn't work. I am happy to say that the system worked perfectly and posted everything exactly as expected.

Code Maroon Emergency Website with Full Alert Information